I just finished The King's Last Song by Geoff Ryman, which I read while in the throes of a head-poundingly miserable virus. This left me in awe not only of Ryman's breathtaking talent but my own ability, even when reading about centuries of war and almost unimaginable human suffering, to maintain a really impressive level of self-pity. I mean, sure, millions of Cambodian people lack the basic necessities of life and have lost family members and the situation is horrifying, but I feel like I have spikes being driven into my ears, I've pulled every muscle in my torso coughing, and I am a dictionary, nay, a veritable encyclopedia of snot. It's all about my pain, people.

I've only ever written (e-mailed) three fan letters, and they've all been to fantasy writers. My husband says he always wants to meet people he admires, because he has this fantasy that he'll be able to come up with something witty and brilliant to say that will impress them and make him memorable. The only time I've ever handed an author I loved a book to be autographed, I just stood there beaming like a slightly backward three-year-old after one too many trips to the sundae bar until she cleared her throat politely and said "um... what's your name?"

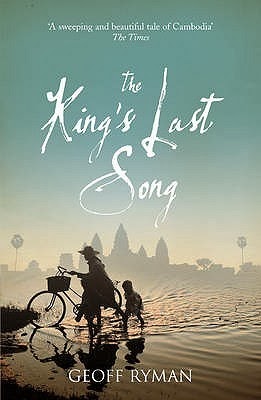

Anyway, one of my fan letters was to Geoff Ryman for his book The Child Garden, which was amazing -- one of the few books that made me feel like I'd truly never read anything like this before. He wrote back and was very gracious (all three of them were). Unfortunately (for me) I didn't love his next few books as much. Still, one of the things I admired about him was how he could differ in style and approach so much from book to book -- he's the furthest thing you can find from a formulaic writer. The Child Garden was fantasy -- subversive and thought-provoking fantasy, dealing with themes of social engineering, thought control and repression, among others. The King's Last Song moves between fiction and historical fiction. The modern narrative deals with the archaeological discovery of an ancient book written on gold leaves at Angkor Wat. Luc Andrade, a professor who grew up in Cambodia, is kidnapped along with the book. William, Andrade's motoboy, guide and friend, and Map, an ex-Khmer Rouge member, are two of the men involved in the attempt to rescue Andrade and the book. The other narrative is the story of Jayavarman VII, the Buddhist King who ruled Cambodia in the twelfth century.

Usually when a book alternates narratives, especially one in the present with one in the distant past, I find myself rushing through one of them in order to get back to the other. I didn't feel that way in the least with this book -- both stories are equally riveting, and wrenching. Perhaps Ryman's greatest strength is his characterization. His characters are so fully realized, so nuanced and multi-dimensional, that you can almost see them right in front of you. There are no types here -- good people commit unthinkable atrocities, and evil men are capable of amazing feats of generosity. Ryman also evokes Cambodia vividly, its heat and beauty and poverty and desperation.

I've heard that connecting something you're learning with a strong emotion makes it much more likely that you'll retain it. I feel as if the events and characters in this book are burned into my mind permanently. Luc Andrade, the French professor who grew up in Cambodia -- he's taken prisoner, held hostage and in fear for his life, and he still cares more about the people of Cambodia and protecting the book than he does about himself. William, the touchingly earnest motoboy who keeps files on everyone he meets in order to learn from them, who "buys fruit and offers you some, relying on your goodness to pay him back. When you do, he looks not only pleased, but justified." Map, who confronts every situation with a frightening zeal and hilarity, who acts with the single-minded fearlessness of someone who has nothing at all left to lose. Jayavarman, the prince who becomes a slave and then a King, a rare King who thinks about the lives and needs of all of his people. Jayarajadevi, his first wife, wise and enlightened but tormented by the need to accept the second wife he brings home from his period of enslavement. Rajapati, the king's son, born with twisted legs and struggling to temper his bitterness by finding a way to be useful.

Nothing happens the way you expect it to in this book, which I guess is also one of the themes. At one point it says that 1985 was the worst year of Map's life, and then a number of good things happen, which naturally you read with a sick feeling of foreboding because clearly something horrifying is coming. The Khmers Rouges committed unthinkable atrocities, and yet many of them were just poor, uneducated young boys who joined the army out of desperation or ignorance. The book is full of searing moments of honesty and unlikely friendships that make small redemptions seem possible, in the midst of despair, which seems the very best one can hope for (for which one can hope?) It is a passionate, eloquent, moving, disturbing story. I am now going to buy a copy (I got it from the library) and obnoxiously demand that everyone I know read it.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Books Read in 2025: The Five-Stars

I forgot to look at the author distribution of the book I read last year at the beginning of these. Out of 191 books, 131 were by women - fa...

-

I don't know how to do this other than as a sprawling, messy, off-in-all-directions thing. I can't do book reviews like Emily, who h...

-

" My Mom got a speeding ticket because she was looking at garage sales." "You don't have to poo on me!" "This...

-

191 books as of 9:21 p.m. on December 30th. I don't think I'm going to finish anything tonight, and we're having a party tomor...

3 comments:

I miss reading. A lot! One day, when all the afghans are made, I plan on reading an entire book before picking up my crochet hooks again! Oh, one can dream!

Ever listen to books on tape while you crochet? I know it's not the same, but the right book with the right reader can be a nice experience. If your kids will leave you alone :)

Sounds interesting. I'll just add it to the quite lengthy list of books I will wait for at the library that will all come in at once.

Post a Comment