Crap.

She's discovered that the Parental Prohibition is completely based on the child's unthinking acceptance of said parent's authority. Dude, we are so screwed.

We were just putting her to bed and she informed us that she just had "the worst day ever" BECAUSE: Angus got to have a friend over and she didn't (because that friend walked over from down the street and Eve has a bit of a cold); she has a cold; she got the hiccups two times; and when she tried to have fun with Jon (the friend) he accidentally dropped the hockey stick on her hand. Matt said well, cheer up, it's virtually impossible to have the worst day ever two days in a row and she gave him this look, like "yeah, you say to cheer up, and yet there's nothing really cheering me up. My entire belief system is built on a facade! Are you even my real father?!". Screwed.

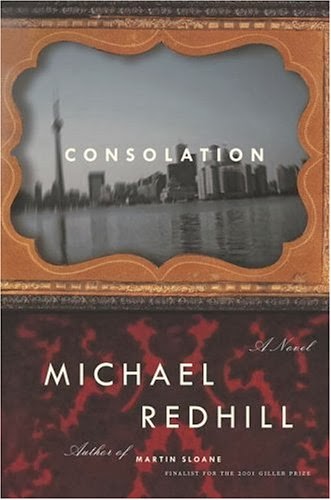

Consolation by Michael Redhill

History, memory, loss. This is a beautiful book, a kind and careful story, even if any comfort it holds is of the cold variety. David Hollis is a forensic geologist who claims to have discovered a diary indicating a lost photographic record of 1850s Toronto. As the primary narrative opens, Hollis commits suicide due to his advancing ALS (Lou Gehrig's Disease). His wife Marianne then takes up residence in a hotel room which overlooks a construction site wherein David believed the photographs were buried due to a shipwreck; this she terms "an interesting reaction to the death of (her husband)". Her daughter's fiance John, a gentle but rather aimless man, begins visiting her and helping her research David's theory, even though this endangers his relationship with Marianne's daughter Bridget.

The second narrative concerns Jeremy Hallam, a pharmacist who comes to Toronto from London in 1855. He hopes to make a thriving business out of his apothecary, making his father proud and earning enough to bring his father and two daughters to Toronto. He is unprepared, though, for the squalid wildness of young Toronto, the poverty and desperation of his fellow citizens. He is unable to sustain the pharmacy and, through a series of events, ends up living and working with Sam Ennis, a dissolute but generous-hearted portrait photographer, and Claudia Rowe, a widow who Hallam first meets posing nude for Ennis.

The relationship between Marianne and John is complex and refreshingly devoid of sentimentality. Both Marianne and Bridget are very prickly and demanding, which may be exacerbated by the fact that they are mourning, but seems to be part of their respective personalities. The description of John navigating dangerous conversations with Bridget, trying to anticipate and defuse potential verbal landmines (and usually failing), is letter-perfect, and would be funny if it wasn't kind of painful and sad (and sadly familiar). John comes into his own helping Marianne, moving out of feeling that he is "an uncharged particle, a conduit through which a force could travel but not remain". David, a man besieged by the overbearing attentions of loving women, most likely contributed to this by treating John as a son and a friend, and communicating his passion for history. Marianne tells a reporter that "(David) thought modern people were the loneliest people in the history of the world. And the thought that another time was under the one we live in was moving to him. Because it's a kind of company for us, all of us marooned here in the present." The resolution of the various relationships, and David's discovery, is neither neat nor wholly satisfying, which is absolutely appropriate to the story.

Equally resistant to easy closure is the story of Jeremy Hallam, Claudia and Ennis. On the surface, it is a fortuitous coming together of three lost souls, an encouraging story of community in the midst of hardship. Indeed, Claudia Rowe and Sam Ennis are cheerful enough in the face of their cramped living quarters and Sam's failing health. However, Hallam is unable to overcome his feelings of failure, his conviction that he has been reduced morally by the city, that he has failed his father and his wife and children. Although their photography business thrives, he is possessed by the conviction that the "the city was a patchwork of damage enlivened by defiant architecture and freshly painted signs".

I can't think of an easy way to sum up this book. It's about people thrashing around half-blind in the midst of time passing and people lost, people searching history for answers to the same questions we still ask, people finding whatever consolation is available in what we have been given.

She's discovered that the Parental Prohibition is completely based on the child's unthinking acceptance of said parent's authority. Dude, we are so screwed.

We were just putting her to bed and she informed us that she just had "the worst day ever" BECAUSE: Angus got to have a friend over and she didn't (because that friend walked over from down the street and Eve has a bit of a cold); she has a cold; she got the hiccups two times; and when she tried to have fun with Jon (the friend) he accidentally dropped the hockey stick on her hand. Matt said well, cheer up, it's virtually impossible to have the worst day ever two days in a row and she gave him this look, like "yeah, you say to cheer up, and yet there's nothing really cheering me up. My entire belief system is built on a facade! Are you even my real father?!". Screwed.

Consolation by Michael Redhill

History, memory, loss. This is a beautiful book, a kind and careful story, even if any comfort it holds is of the cold variety. David Hollis is a forensic geologist who claims to have discovered a diary indicating a lost photographic record of 1850s Toronto. As the primary narrative opens, Hollis commits suicide due to his advancing ALS (Lou Gehrig's Disease). His wife Marianne then takes up residence in a hotel room which overlooks a construction site wherein David believed the photographs were buried due to a shipwreck; this she terms "an interesting reaction to the death of (her husband)". Her daughter's fiance John, a gentle but rather aimless man, begins visiting her and helping her research David's theory, even though this endangers his relationship with Marianne's daughter Bridget.

The second narrative concerns Jeremy Hallam, a pharmacist who comes to Toronto from London in 1855. He hopes to make a thriving business out of his apothecary, making his father proud and earning enough to bring his father and two daughters to Toronto. He is unprepared, though, for the squalid wildness of young Toronto, the poverty and desperation of his fellow citizens. He is unable to sustain the pharmacy and, through a series of events, ends up living and working with Sam Ennis, a dissolute but generous-hearted portrait photographer, and Claudia Rowe, a widow who Hallam first meets posing nude for Ennis.

The relationship between Marianne and John is complex and refreshingly devoid of sentimentality. Both Marianne and Bridget are very prickly and demanding, which may be exacerbated by the fact that they are mourning, but seems to be part of their respective personalities. The description of John navigating dangerous conversations with Bridget, trying to anticipate and defuse potential verbal landmines (and usually failing), is letter-perfect, and would be funny if it wasn't kind of painful and sad (and sadly familiar). John comes into his own helping Marianne, moving out of feeling that he is "an uncharged particle, a conduit through which a force could travel but not remain". David, a man besieged by the overbearing attentions of loving women, most likely contributed to this by treating John as a son and a friend, and communicating his passion for history. Marianne tells a reporter that "(David) thought modern people were the loneliest people in the history of the world. And the thought that another time was under the one we live in was moving to him. Because it's a kind of company for us, all of us marooned here in the present." The resolution of the various relationships, and David's discovery, is neither neat nor wholly satisfying, which is absolutely appropriate to the story.

Equally resistant to easy closure is the story of Jeremy Hallam, Claudia and Ennis. On the surface, it is a fortuitous coming together of three lost souls, an encouraging story of community in the midst of hardship. Indeed, Claudia Rowe and Sam Ennis are cheerful enough in the face of their cramped living quarters and Sam's failing health. However, Hallam is unable to overcome his feelings of failure, his conviction that he has been reduced morally by the city, that he has failed his father and his wife and children. Although their photography business thrives, he is possessed by the conviction that the "the city was a patchwork of damage enlivened by defiant architecture and freshly painted signs".

I can't think of an easy way to sum up this book. It's about people thrashing around half-blind in the midst of time passing and people lost, people searching history for answers to the same questions we still ask, people finding whatever consolation is available in what we have been given.

No comments:

Post a Comment