I'm a little foggy on the notion of what constitutes a 'classic', in truth. Pearl S. Buck won the Nobel Prize in Literature - does that mean every single thing she wrote is automatically a classic? I'm choosing to think so. In my mind 'classic' often means something I feel guilty for not having read, which is not a great state of mind in which to undertake reading something, but there it is.

The Eternal Wonder by Pearl S. Buck: A recently discovered novel written by Pearl S. Buck at the end of her life in 1973, The Eternal Wonder tells the coming-of-age story of Randolph Colfax (Rann for short), an extraordinarily gifted young man whose search for meaning and purpose leads him to New York, England, Paris, on a mission patrolling the DMZ in Korea that will change his life forever—and, ultimately, to love.

Rann falls for the beautiful and equally brilliant Stephanie Kung, who lives in Paris with her Chinese father and has not seen her American mother since she abandoned the family when Stephanie was six years old. Both Rann and Stephanie yearn for a sense of genuine identity. Rann feels plagued by his voracious intellectual curiosity and strives to integrate his life of the mind with his experience in the world. Stephanie struggles to reconcile the Chinese part of herself with her American and French selves. Separated for long periods of time, their final reunion leads to a conclusion that even Rann, in all his hard-earned wisdom, could never have imagined.

A moving and mesmerizing fictional exploration of the themes that meant so much to Pearl S. Buck in her life, this final work is perhaps her most personal and passionate, and will no doubt appeal to the millions of readers who have treasured her novels for generations.

| I got the Kindle version of this because it was cheap and I had a vague feeling that I should read something by Pearl S. Buck, sort of when I thought I should read something by Truman Capote but I was too cool or something for In Cold Blood, so instead I read Summer Crossing which was okay, but I always seem to pick books by famous people and then find out that it's actually some manuscript unearthed after the author's death and the publication of it was hotly contested by the heirs. With Pearl S. Buck I could have almost certainly chosen a better place to start. I almost gave up after the first few pages which described Rann's conception and incubation in exhaustive, excruciating detail. The whole thing had a sort of 'this happened, then this happened, then this' tedium to it. The description of a prodigious intelligence seeking to find its place in the world holds a certain interest, but overall this was a little underwhelming. |

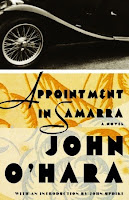

Appointment in Samarra by John O'Hara: O’Hara did for fictional Gibbsville, Pennsylvania what Faulkner did for Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi: surveyed its social life and drew its psychic outlines, but he did it in utterly worldly terms, without Faulkner’s taste for mythic inference or the basso profundo of his prose. Julian English is a man who squanders what fate gave him. He lives on the right side of the tracks, with a country club membership and a wife who loves him. His decline and fall, over the course of just 72 hours around Christmas, is a matter of too much spending, too much liquor, and a couple of reckless gestures. That his calamity is petty and preventable only makes it more powerful. In Faulkner, the tragedies all seem to be taking place on Olympus, even when they’re happening among the low-lifes. In O’Hara, they could be happening to you.

Appointment in Samarra by John O'Hara: O’Hara did for fictional Gibbsville, Pennsylvania what Faulkner did for Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi: surveyed its social life and drew its psychic outlines, but he did it in utterly worldly terms, without Faulkner’s taste for mythic inference or the basso profundo of his prose. Julian English is a man who squanders what fate gave him. He lives on the right side of the tracks, with a country club membership and a wife who loves him. His decline and fall, over the course of just 72 hours around Christmas, is a matter of too much spending, too much liquor, and a couple of reckless gestures. That his calamity is petty and preventable only makes it more powerful. In Faulkner, the tragedies all seem to be taking place on Olympus, even when they’re happening among the low-lifes. In O’Hara, they could be happening to you. Oh look, I didn't review this one. I actually do remember quite a bit of it, and I didn't love reading it, which is fine because I'm pretty sure that wasn't the point, but it was definitely affecting, in a profoundly depressing kind of way. Much like with Holden Caulfield, I didn't entirely agree with the assessment that Julian English was a man who 'squanders what fate gave him'. He just seemed lost and sad, and it made me feel lost and sad. The time period and class circumstances were vividly rendered. I was really, really glad that I was not any of these people.

Fiction:

A Fine and Private Place by Peter S. Beagle: This classic tale from the author of The Last Unicorn is a journey between the realms of the living and the dead, and a testament to the eternal power of love.Michael Morgan was not ready to die, but his funeral was carried out just the same. Trapped in the dark limbo between life and death as a ghost, he searches for an escape. Instead, he discovers the beautiful Laura...and a love stronger than the boundaries of the grave and the spirit world.

I just read that Peter S. Beagle wrote this when he was NINETEEN FREAKING YEARS OLD. And it wasn't perfect, but now that I'm thinking about it the ways in which it was imperfect sort of made it all that more perfect. It doesn't unfold exactly how you expect it to, which is kind of refreshing. It describes being dead in a way that seems eminently probable. I always think that Peter S. Beagle's writing makes it seem like he's the kind of person who views the world and all the people in it in the kindest possible light. This book didn't change that opinion.

Truly Madly Guilty by Liane Moriarty: Six responsible adults. Three cute kids. One small dog. It’s just a normal weekend. What could possibly go wrong?

Truly Madly Guilty by Liane Moriarty: Six responsible adults. Three cute kids. One small dog. It’s just a normal weekend. What could possibly go wrong?Sam and Clementine have a wonderful, albeit, busy life: they have two little girls, Sam has just started a new dream job, and Clementine, a cellist, is busy preparing for the audition of a lifetime. If there’s anything they can count on, it’s each other.

Clementine and Erika are each other’s oldest friends. A single look between them can convey an entire conversation. But theirs is a complicated relationship, so when Erika mentions a last minute invitation to a barbecue with her neighbors, Tiffany and Vid, Clementine and Sam don’t hesitate. Having Tiffany and Vid’s larger than life personalities there will be a welcome respite.

Two months later, it won’t stop raining, and Clementine and Sam can’t stop asking themselves the question: What if we hadn’t gone?

In Truly Madly Guilty, Liane Moriarty takes on the foundations of our lives: marriage, sex, parenthood, and friendship. She shows how guilt can expose the fault lines in the most seemingly strong relationships, how what we don’t say can be more powerful than what we do, and how sometimes it is the most innocent of moments that can do the greatest harm.

| Not the usual out-of-the-park home run that Moriarty often is for me. I like the way she dwells on and elasticizes domestic details, but here I just felt like she tried to make too much out of too little. Okay, now that seems uncharitable given that none of the individual issues were small, but the story didn't feel as expansive and rich as her other work, and the ostensible twist is kept too long and feels manipulative and unkind. There were still little moments that felt perfectly real and wonderful. |

| The writing style held my interest, and the very first part does a fair job of setting up the reveal, but I felt like too much was revealed too early which caused all the tension to leak out of the rest of the book. I had the impression that I was expected to be more shocked and appalled than I was, as if the author was terribly impressed with how daring and alternative he was being, which smacked - possibly unfairly - of adolescent gimmickry. |

The Peculiar Memories of Thomas Penman by Bruce Robinson: The cult classic novel of growing up in 1950s England from the writer of Withnail and I.

| This was on my book club list. I really didn't enjoy it. It actually made me feel faintly nauseous on more than one occasion. Even looking at the cover now still makes me uncomfortable. Then I read that it might be autobiographical, and somehow it makes it better if it's not fiction. Still gross, but not gross on purpose, I guess. It definitely conveys a vivid sense of being alive in that time, stuck between warring parents and desperate for freedom, romance and pornography. I have to go take a shower now. |

Non-Fiction:

Death in a Prairie House: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Murders by William R. Drennan: The most pivotal and yet least understood event of Frank Lloyd Wright’s celebrated life involves the brutal murders in 1914 of seven adults and children dear to the architect and the destruction by fire of Taliesin, his landmark residence, near Spring Green, Wisconsin. Unaccountably, the details of that shocking crime have been largely ignored by Wright’s legion of biographers—a historical and cultural gap that is finally addressed in William Drennan’s exhaustively researched Death in a Prairie House: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Murders.

Death in a Prairie House: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Murders by William R. Drennan: The most pivotal and yet least understood event of Frank Lloyd Wright’s celebrated life involves the brutal murders in 1914 of seven adults and children dear to the architect and the destruction by fire of Taliesin, his landmark residence, near Spring Green, Wisconsin. Unaccountably, the details of that shocking crime have been largely ignored by Wright’s legion of biographers—a historical and cultural gap that is finally addressed in William Drennan’s exhaustively researched Death in a Prairie House: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Murders.In response to the scandal generated by his open affair with the proto-feminist and free love advocate Mamah Borthwick Cheney, Wright had begun to build Taliesin as a refuge and "love cottage" for himself and his mistress (both married at the time to others).

Conceived as the apotheosis of Wright’s prairie house style, the original Taliesin would stand in all its isolated glory for only a few months before the bloody slayings that rocked the nation and reduced the structure itself to a smoking hull.

Supplying both a gripping mystery story and an authoritative portrait of the artist as a young man, Drennan wades through the myths surrounding Wright and the massacre, casting fresh light on the formulation of Wright’s architectural ideology and the cataclysmic effects that the Taliesin murders exerted on the fabled architect and on his subsequent designs. Best Books for General Audiences, selected by the American Association of School Librarians, and Outstanding Book, selected by the Public Library Association.

I didn't come out of this book feeling like the event in question was the least bit more understood. I picked it up in the library because I was interested in reading about Frank Lloyd Wright and I've always found the figure of Taliesin intriguing. As a biography of Wright - clearly a brilliant man and another entry in the catalogue of brilliant people who believe that brilliance entitles one to behave like a self-centered jackass - it was fascinating. The story of the murders was horrible and the question of the motivation was as clear as mud by the book's end. I probably just should have read a straight biography.

The Examined Life: How We Lose and Find Ourselves by Stephen Grosz: Echoing Socrates' time-honoured statement that the unexamined life is not worth living, psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz draws short, vivid stories from his 25-five-year practice in order to track the collaborative journey of therapist and patient as they uncover the hidden feelings behind ordinary behaviour.

These beautifully rendered tales illuminate the fundamental pathways of life from birth to death. A woman finds herself daydreaming as she returns home from a business trip; a young man loses his wallet. We learn, too, from more extreme examples: the patient who points an unloaded gun at a police officer, the compulsive liar who convinces his wife he's dying of cancer. The stories invite compassionate understanding, suggesting answers to the questions that compel and disturb us most about love and loss, parents and children, work and change. The resulting journey will spark new ideas about who we are and why we do what we do.

These beautifully rendered tales illuminate the fundamental pathways of life from birth to death. A woman finds herself daydreaming as she returns home from a business trip; a young man loses his wallet. We learn, too, from more extreme examples: the patient who points an unloaded gun at a police officer, the compulsive liar who convinces his wife he's dying of cancer. The stories invite compassionate understanding, suggesting answers to the questions that compel and disturb us most about love and loss, parents and children, work and change. The resulting journey will spark new ideas about who we are and why we do what we do.

| Interesting, if a little glib. Certain cases felt like Grosz was forcing an analytical framework over life events whether or not it fit well. I was expecting a little more subtlety and depth. The first chapter, which I believe I read in the bathtub (what does that mean?), was a perfect story, truth or fiction - immensely satisfying. |

1 comment:

I just added The Dinner and Truly Madly Guilty to my list!

Post a Comment